- Home

- Cynthia L. Smith

Ancestor Approved Page 9

Ancestor Approved Read online

Page 9

“Jeff will show up soon. I just know it,” Uncle Mutt said.

But, truth be told, Mutt was worried about his kid brother, too. No matter how old they got, Jeff would always be his little brother. And it was Mutt’s job to look after him. “If he doesn’t turn up by lunchtime, we’ll call your grandma back in Minnesota and see if she’s heard from him.”

The night before, as Jeff and Helen approached the clearing where they had seen the odd light dancing on the trees, they heard voices. They could just make out a flurry of activity through the trees ahead.

They stopped at the edge of the trees. Helen gasped when she saw men unloading cargo from muddy ATVs and hauling it toward the trees across from where she and Jeff stood. A small fire burned in the middle of their makeshift camp, throwing fingers of light on the trees that surrounded them. So the odd fire they’d seen hadn’t been a wendigo after all.

The men in the camp moved quickly, unloading deer and hauling them up side by side into the trees by their back legs. There must have been two dozen deer altogether. Large and small. Buck and doe. One of the hunters, a short, bearded man wearing coveralls and work gloves, dressed each deer, one after another, working quickly and quietly by the light of the lanterns that sat on the ground near him. He’d obviously done this before.

What were these guys doing? It wasn’t hunting season.

Poachers!

Jeff signaled for Helen to stay quiet and backed away from the edge of the clearing.

“If we ever find our way back, we’d better get one of the rangers out here,” he said.

“Yeah, that’s not gonna happen,” said a man’s voice out of the darkness. Helen and Jeff jumped as they heard someone rack a shell in a shotgun.

“You’re staying here until we’re done. Then we’ll decide what to do with you.”

The man gestured with his shotgun for Jeff and Helen to sit down. Helen cried softly as she and Jeff sat with their backs to a large tree. Their captor tied their wrists together with a rough length of rope he pulled from the pack on his back.

“Now sit there and be quiet and let us get our work done,” their captor snarled. “Don’t make me haul you up in that tree like one of them deer.”

After the man returned to the clearing, Helen and Jeff sat in silence, afraid to speak. Their shoulders and arms ached. The chill of the ground was working its way up their bodies. They could see the man with the gun talking to the others and gesturing back toward where they sat at the dark edge of the woods. After a brief, excited conversation, the poachers got back to their work.

“What are we going to do?” Helen asked in a whisper.

The forest around them was quiet. They could see the stars above them through the tops of the trees. Helen sniffled. Jeff felt a knot in his stomach and began to shake.

Neither of them could think of a way out of this. And the night was growing colder by the minute.

Just then, a plump, scruffy raccoon waddled out of the underbrush and sat up on its haunches. It tilted its head and looked at Jeff and Helen. It chattered and squeaked at them.

“What’s that you say, gvli?” Jeff said to the raccoon. “vv—halisdela! Yes—help us!”

The raccoon chattered at them some more. She quickly licked and bit both front paws before turning and wandering back into the bushes.

“You don’t think she understood you, do you?” Helen asked Jeff.

“I don’t know why not. My mom always told me that all animals speak Cherokee. That raccoon had a bit of an Ojibwe accent, but I caught the drift of what she was saying. She’s going to get help.”

Despite their predicament, Helen had to smile.

A shiver ran up her spine as she heard coyotes yipping and howling off in the distance.

A moment later, they heard the call of a whip-poor-will.

“See, they’re passing the word,” Jeff said.

“Shhh,” Helen said.

“What?”

“Shhh, I said! Don’t you hear that?”

Footsteps were moving toward them in the darkness. They both strained their eyes as they scanned the dark woods. The footsteps weren’t coming from the direction of the clearing where the poachers continued their work. They were coming from the deeper part of the woods.

Helen’s voice rose. “Do you think it’s a bear?”

Just then a tall, thin, shadowy figure stepped from behind a tree and moved swiftly toward them. Neither could see it clearly or tell whether it was animal or human. It made no sound. Both Helen and Jeff let out a surprised gasp. Before they knew it, the ropes slid from their wrists. They got to their feet, but their rescuer had vanished!

“What the—?” Helen said.

“These ropes weren’t cut,” Jeff said, looking at the pieces in his hand. “It looks like someone burned them. Where did he go? Did you see where he ran off to?”

Helen didn’t answer. Instead she pointed to the top of the trees, where flames leaped away from them.

Jeff nodded. “Wendigo.”

Helen didn’t argue with him. She just said, “Let’s get out of here,” as she grabbed Jeff’s arm and pulled him away from the clearing and into the welcoming darkness of the forest.

“Excuse me,” the deputy said that Saturday afternoon, stepping into the doorway of the gym and stopping in front of Tokala, who was typing away on an iPad Mini. “I’m looking for a man and a boy. Mutt and Jayson Mills?”

“Never heard of them,” Tokala said, pausing her typing and looking up at the deputy with narrowed eyes.

“Well, if you should see them, please let them know we’re looking for them. We’ve found their missing relative, Jeff Mills.”

“Oh, you must mean Jace. I met him earlier when he was looking for his uncle. That’s him over there with his other uncle, standing by the fry bread stand.”

The ride out to the University of Michigan Medical Center in the back of the deputy’s car was the longest ride Jace had ever taken. Flurries danced around the car. The sky was darker than normal.

“But they’re all right, aren’t they?” Uncle Mutt asked the deputy.

“Yes. They’re tired. Cold. A little hungry. But they’ll be fine once we have them checked out by a doctor,” the deputy said. “It’s just a precaution. Neither of them was hurt.”

Jace ran into the room and threw his arms around his uncle, who was sitting in the bed nearest the door. “You had us so worried.” Then he noticed Helen sitting in the other bed, looking at him.

“Hello, young man.”

Jace walked over and shook Helen’s hand. She pulled him down into a hug.

Jeff was starting to get uncomfortable with all the emotion in the room.

“Quite the matching outfits we have on,” he said. He and Helen wore thin hospital gowns, white with small blue flowers.

Helen sat up straighter in the bed and struck a pose.

“You were supposed to be at the powwow with us, not hiking in the woods and chasing bad guys,” Jace said, his voice rising. “What were you thinking, Uncle Jeff?”

“I told you I wanted to look for a wendigo. I wasn’t going to find one at the powwow,” Uncle Jeff said matter-of-factly. “Wendigos don’t dance.”

“The police told us that some poachers had you tied up in the woods. By the time the police got there, the poachers had cleared out. All they found was an abandoned camp and some tire tracks,” Mutt said. “How did you two ever get away? You’re not exactly Houdini.”

Jeff used the controller to raise the back of his hospital bed a bit higher.

“You see, it’s like this,” he began. “It all started when a clever raccoon told a wendigo about our predicament . . .”

Mutt and Jace groaned.

Mutt picked up a pillow off Helen’s bed and tossed it at Jeff. “Shouldn’t you save the stories for the powwow?” he said. “If we leave now, we might get back before they run out of fry bread.”

Indian Price

Eric Gansworth

�

�It’ll be fun,” my mom said, which meant, for sure, it wouldn’t be. We’re small-time Indian craft vendors, setting up at powwows and socials in Upstate New York, Ontario, and Quebec. In addition to regular beadwork items like key chains and glasses cases, my mom makes whatever wild thing her imagination offers. My dad makes ribbon shirts and breechcloths. Owners like custom details, but he always brings samples. We’re good enough that we can usually count on nearly empty bins coming home to the Rez, just outside Niagara Falls.

Lately, we’ve requested “Golden Booths,” with a view of dancers and close to food vendors and bathrooms. Partly it’s because we do well enough, sales-wise, but we also do it so my dad doesn’t have to walk far. We keep quiet about this, but we know, and worse, he knows.

When my mom told me we were going to Michigan, I thought we’d be staying at a hotel. Hot tubs are good for my dad, and when white people see us coming, they usually decide they don’t need to enjoy it anymore and go back to their own rooms.

My dad says they’re scared of the scars on his legs, but even at thirteen, I know better. They’re afraid our ethnic germs are gonna throw off the chlorine and sneak up on them.

Turned out we were staying with my mom’s brother. Uncle Dave worked custodial at the high school where this powwow was held. He said he’d lucked out on his first workday. His boss, a guy named Mike, amazingly was also Indian. Turtle Mountain Ojibwe. It might seem like a small thing, but there aren’t a ton of us around once you move off the Rez. Uncle Dave’s wife, Florence, worked at the university, a professor, my mom always reminded me. Florence and their boy, Potter, used to come when Uncle Dave visited our Rez, where my ma and Uncle Dave were raised, but they gradually stopped, and no one speaks of it.

“Now remember, call her Auntie Florence,” my mom said once we got on the road. On the Rez, you call women auntie who you aren’t even related to. It’s the ones who act like your real aunties when they aren’t even, telling you secrets your parents don’t want you to know, embarrassing you at a party, just to show they can. Lately, when the Rez aunties see me, they make a big show of putting their cigs and lighters in their beaded purses and clutching them. As if I’d steal their nasty Rez-brand smokes. They know I don’t smoke. They’re just telling me: No Wampum Incident repeats!

“Did you take inventory before we left?” my dad asked.

“I’ll take it again,” I said, so he would hear: I’ll remember to call her Auntie. It was going to be challenging enough to call my cousin by his name. Who names their kid “Potter,” anyway? It would be like me being named Roofer (or ex-Roofer).

See, Uncle Dave paid the bills with his custodian job, but he was also a potter, making traditional open-pit-fired clay pots. He even had pieces in museums that didn’t want our work.

Whenever Uncle Dave talked my mom into applying for fellowships and they told her no thanks, they said her work didn’t fit into categories. It’s not traditional enough to be “folk art,” and it’s too traditional to be “contemporary.” Or like my dad says: If people can understand it when they first look, they think it’s not sophisticated enough. It never even occurs to them that it’s just the doorway into the bigger ideas. And if it doesn’t look like a Pendleton blanket, then they think the designs aren’t Indian enough.

Like a lot of brothers and sisters, they’ve argued this for so long, they sometimes can’t remember which side they’re on. Uncle Dave thinks she should make work that’s harder to understand, and then he backs off, saying it needs to be more basic. His stuff sells better because it doesn’t cost as much, and he puts in enough obvious signs that say INDIAN ART HERE, and people know what it’s supposed to be, right away. He says if white people are purposely shopping for Indian stuff, your stuff better include lots of feathers and geometry, if you hope to make a sale.

“What the heck is this?” I pulled up a long, narrow gift box hidden in a folded Pendleton blanket we used as a table cover. It was shut tight with my mom’s signature fancy ribbon ties.

“Just leave it,” my mom said. “And when we get there, put it in Potter’s room.” She was being cagey.

My parents believed I should know the whole business: inventory, hang-tag pricing, the change box, and the secret change box underneath, where we kept bigger bills.

The one thing I had the hardest time mastering was Indian Price, the most important part of being a powwow arts-and-crafts vendor. This was the slightly lower price you gave to someone you knew was definitely Indian, but this rule took me forever to understand.

At Uncle Dave’s, my parents stayed in the “guest room,” a room where only dust bunnies lived. The whole house was decked out in “authentic Indian art,” from vendors with tribal proof for the Indian Arts and Crafts Act. My mom says this law means you can’t call something for sale “Indian made” if it wasn’t actually made by an Indian. A law about not lying, I guess. Most powwows enforced it. I said all it took was eyes to tell we were “authentic Indians.” My mom reminded me that not everything is that simple.

“We thought you might want to stay with Potter,” Auntie Florence said. “He and his friends are in your uncle Dave’s ‘man cave.’ They’re dancing tomorrow and want to practice.”

Potter was going to dance? Maybe he’d made inroads with the Indians that Uncle Dave says are scattered around Detroit. “Or you can stay in his room. You’re old enough to make your own decisions now,” she said, smiling. She definitely knew about the Wampum Incident.

At least she wasn’t going to act like the Rez aunties. Maybe instead, she was just going to make sure their valuables were away in a giant safe.

Potter was seventeen, so he wouldn’t want some middle school kid hanging around. I chose his room. It also had crafts everywhere, but his stuff seemed to come from a ton of territories. Like a bunch of Indians from around the country had exploded in this room.

I snuck my mom’s fancy ribbon off that mystery gift. Years of practice left me able to peek without anyone knowing different. Inside was a loop of hide, like Chewbacca’s bandolier. Weird. My mom rarely worked white hide leather. The beadwork was unusual, too. A foot-long single arrow, solid red glass beads, with the point at the top.

An included note card had a turtle on it, like you see at any powwow vendor area. Generic “Indian designs.” Feathers and geometry, like my dad says. Customers often sent a card with payment so my mom could seal it in before doing her ribbon magic. This card was someone else’s privacy, but I had to know.

Congratulations on your election to the Order of the Arrow and your successful call-out and Ordeal! We are so very proud you stuck to this! We know it wasn’t easy.

Love, Mom and Dad

This commission was a gift was for Potter from my uncle and auntie. But Order of the Arrow? What could that possibly be? I was also curious about how you could get “called out” successfully. Being called out for the Wampum Incident was definitely not a happy time for me. It must mean something different to the Arrow Order guys.

Someone bounded up the stairs and knocked.

I laid my bag on the box as Potter opened the door a crack.

“Hey, Dalton,” he said, just visible. “Mind if I come in?”

“It’s your room,” I said, hearing my own grumpiness. “Nyah-wheh for letting me use it.”

“Sure, but you’re welcome to join us,” he said. His hair was longer than two years ago, touching his shoulders. Still, it was as pale as corn silk. “Just Xbox and junk food. Some guys in our troop think being a Scout means being perfect all the time, always doing something for others, but sometimes you just wanna hang with friends.”

“Troop?”

“You didn’t stick with Scouts?” When I signed up for Cub Scouts, the Rez leader switched our meetings from Wednesday nights to eight o’clock Saturday mornings. That killed scouting on the Rez.

“Anyway, we’re getting in the hot tub if you wanna join. Just five of us. Plenty of room. Loosen our muscles.” I told him I had stuff to do, but he set ou

t a pair of Crocs, a towel, and a set of trunks he’d outgrown, in case I changed my mind. A while later, he and his friends were laughing, and my need to be an Indian and join my group was too strong, even if this wasn’t really my group.

The air was sharp, though I had a towel around my shoulders. Potter and his friends slid the hot tub cover off and jumped in. Indians come in a big range of colors and looks, but his four friends looked pretty strictly white. I had the feeling I was the only actual Indian here, with Potter as a close second.

“Man, this is worse than my Ordeal,” one named Craig said, and the rest laughed, a private joke. “Come on up, Little Man,” Craig said, moving. It felt weird to wear someone else’s trunks, but if you had to, it was best they belonged to your cousin.

The water was hot, and the wind blasted sharp air, each half of me getting a different extreme signal. I settled in, just my head and neck above water.

“Harry, you didn’t turn the jets on?” Craig asked, and Potter stood. These guys seemed to like each other fine, but clearly Craig was the one they looked up to.

“Harry?” I asked. “I’ll do it,” I said, climbing out. Even after a minute underwater, I felt insulated. The air wasn’t as painful. I turned the timer dial on the deck and hopped back in.

“H-A-I-R-Y,” Craig clarified. “Since your cousin grew his hair out, that’s what we call him.” Hairy Potter, I thought, almost a Rez-worthy nickname.

“You sure are a red man, now, Little Man,” Craig added. Apparently, nicknames were his thing. My blood had rushed to the surface in this March air, making my brown skin look like a very ripe peach. I gave Hairy Potter a sideways eye snap.

Potter raised his eyebrows in the center, like keyboard accent marks, silently asking me not to sass. His house, his rules. Two of the others started practicing their secret greeting, but Craig cleared his throat and they stopped.

Like I cared and was going to quick run out and tell the world.

Ancestor Approved

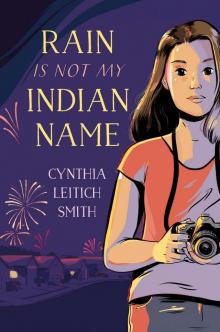

Ancestor Approved Rain Is Not My Indian Name

Rain Is Not My Indian Name