- Home

- Cynthia L. Smith

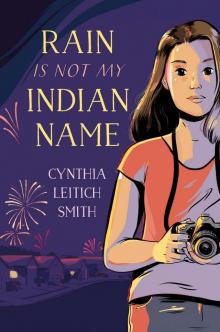

Rain Is Not My Indian Name

Rain Is Not My Indian Name Read online

Dedication

FOR MY COUSIN,

FILMMAKER ELIZABETH MCGEHEE

With appreciation to: Kathi and Ken Appelt; Ann Arnold; Christopher T. Assaf; Haemi Balgassi; Franny Billingsley; Mr. Bolton (ninth grade); BookPeople of Austin, Texas; Toni Buzzeo; Gilbert Cavazos; Nora Cleland; Stacy and Todd Cohen; Penny and Ron Cooper; Carolyn Crimi; Betty X. Davis; Meredith Davis; Tiffany Durham; Tom Eblen; Staci Gray; Peni R. Griffin; James Hendricks; Esther Hershenhorn; Jennifer Hibbs; Frances Hill; Jane Kurtz; Debbie Leland; Daveen Litwin; Gail McCauley; Michelle McLean; the Mid-Continent Public Library of Grandview, Missouri; Marisa Miller; Nicole Moreno; Linda Mount; Ellen Oh; Carmen Oliver; Nicole Onsi; Mr. Pennington (twelfth grade); the Pod; Gayleen Rabakukk; Mr. Rideout (sixth grade); Polly Robertus; Harlan Roedel; Tracy Russell; Sara Schachner; Heather Slotnick; Bud and Caroline Smith; Dorothy P. Smith; Greg Leitich Smith; Courtney Stevenson; Mary Wallace; We Need Diverse Books; Jerry Wermund; Melba and Herb Wilhelm; Mrs. Woodside (first grade); Kathryn Zbryk; the Texas children’s literature community; Toad Hall Children’s Bookstore; my gray tabby cats, Mercury and Sebastian; my Chihuahua, Gnocchi; and especially Anne Bustard, for pep talks and playing midwife; and as always Ginger Knowlton, agent extraordinaire, and Rosemary Brosnan, editor-mentor-friend-confidante-blessing. And most recently, mvto to cover artist Natasha Donovan for beautifully conveying Rain’s thoughtful nature, her gentle humor, and the spirit of her story and small-town community.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Tasty Freckles

Broken Star

Six Months Later

My Not-So-Secret Secret Identity

Moo Shu and Peace

Indian Camp

Malibu Pocahontas

Her Mother’s Daughter

Trailer Park Dreams

Stop the Presses

A Taste for Green Bean Casserole

Did Somebody Say “Clueless”?

Rising Rain

Mamas and Babes

Deadlines

Independence Day

Children of the Corn

What Really Happened

Author’s Note

About the Author and Illustrator

Books by Cynthia Leitich Smith

Back Ad

Copyright

About the Publisher

Tasty Freckles

FROM MY JOURNAL:

On New Year’s Eve, I stood waiting my turn in the express aisle of Hein’s Grocery Barn, flipping through the December issue of Teen Lifestyles.

The magazine reported: “76% of teenagers who responded to our Heating Up Your Holidays survey indicated that they had French-kissed someone.”

The next day was my birthday, and I’d never kissed anyone—domestic-style or French. Right then, looking at that magazine, I decided to get myself a teen life.

Tradition was on my side. Among excuses for kisses, midnight on New Year’s Eve outweighs mistletoe all Christmas season long. Kissing Galen would mark my new year, my birthday, my new beginning.

Or I’d chicken out and drown in a pit of humiliation, insecurity, and despair. Cassidy Rain Berghoff, Rest in Peace.

DECEMBER 31

That night, Galen and I jogged under the ice-trimmed branches of oaks and sugar maples, never guessing that somebody was watching us through ruffled country curtains and hooded miniblinds. We should’ve known.

Small-town people make the best spies.

As we tore through the parking lot behind Tricia’s Barbecue House, my camera thudded against my hip and I breathed in the chill, the mist, and the spicy smell of smoking beef. Galen’s cold hand yanked mine past Phillips 66 Car Wash, Sonic Drive-In, and up the tallest hill in town to N. R. Burnham Elementary. Chewie, my black Lab, led us to the playground, and Galen grinned at me like we were getting away with something.

I thought we were.

Of course Grampa Berghoff hadn’t given us permission to prowl like night creatures on New Year’s Eve. Earlier that evening, he’d shelled out twenty-five bucks for pizza delivery and entertainment, and said, “Watch yourself.”

But Galen drew his line at rom-coms, and I drew mine at Anime. Mercury Videos, CDs & Vintage Vinyl was a fun place to kill time, but there was hardly anything new in stock since our last visit.

Galen and I had gone out after the third phone call from his mother: the first to ask if he’d gotten to my house okay, a whopping five blocks; the second to ask if my big brother, Fynn, could drive Galen home—no problem; and finally to ask if Grampa and Fynn would be back from their dates before midnight. As if.

My high-tops smacked the playground asphalt, and I opened my mouth to catch a snowflake or two. Galen let go of my hand, and I dropped into the swing beside him.

We soared.

Below, Christmas lights outlined rooftops, shop windows, and the clock tower on the Historical Society Museum of Hannesburg, Kansas. Cottony smoke puffed out of chimneys and blurred into clouds. Plastic reindeer hauled Santa’s sleigh on top of the new McDonald’s.

Perfect, I thought.

Besides haunting the streets and swinging to the heavens, I planned to try out the filters Grampa had tucked into my Christmas stocking the week before. I hoped to compose some shots of my hometown in all of its hazy holiday glitter.

But that’s not what I was nervous about.

Glancing at Galen, I could still see my field trip buddy, the one who’d tugged me away from Mrs. Bigler’s second-grade class to find turquoise cotton candy at the American Royal Rodeo. I wasn’t a hard sell. With my parents’ pocket camera ready, I’d hoped to shoot whatever wasn’t on the guided tour. When we finally got caught, Mrs. Bigler sentenced us both to keep our noses to the brick wall for a month of recesses.

Through lemonade stands, arcade games, spelling bees, and science fairs, we’d been best friends ever since.

When Galen’s rock busted out the new streetlight, we both got a tour of the city lockup. When Galen climbed the water tower and couldn’t get back down, I’m the one who called the volunteer fire department.

But at Mom’s funeral, he was the one who answered for me when people said they were sorry and what a shame. “Thank you for coming,” he told them, just like a grown-up. And he’d asked Gramma Scott to check on me after I’d gone into the funeral home restroom and decided to never come out.

Galen was the one person who always understood me, the one person I always understood.

Over the past couple of years, though, something had happened. Something unexpected. Something that made me feel squishy inside. Galen’s bangs had draped to the nub of his nose. His sweeping golden eyelashes made my stubby dark ones look like bug legs. He’d grown so delicious, I longed to bite the freckles off of his pink cheeks.

As Chewie barked at us from the playground below, I shivered on my swing and scolded myself for leaving the house in only my ladybug-patch jeans and the black silk blouse Aunt Louise had sent me for Christmas. But the silk made me feel more sophisticated somehow, and I’d worn it, figuring I could use all the attitude I could get.

My watch read twelve minutes until midnight. “Almost time,” I announced.

“Hey, birthday girl,” Galen called, “guess what I got you.”

“I told you ten times that I give up,” I answered, pumping my legs, trying to outswing him. “Besides, I’ll find out tomorrow.”

Galen and I had both been holiday babies with birthdays outside of the school calendar, and so sometimes people forgot about celebrating us. That’s why he’d promised to always remember my birthday, New Year’s Day, and I’d promised to always remember his, the Fourth of July. We’d spit-shook on it.

Galen’s taste in presents, though, was adventurous. Over the past few years, he’d given me a frog skeleton, a bag of rock-hard gum balls, and a midnight blue Avon perfume bottle swiped from his mom’s bathroom. Last year, he’d gotten ahold of eleven cardboard stand-ups of Star Trek characters and talked eleven downtown merchants into featuring them in the shops’ storefront window displays. Each stand-up held a sign reading TELL RAIN BERGHOFF, “HAPPY BIRTHDAY.”

I’d been so embarrassed that I didn’t leave home for a week. Four months later, people had still been wishing me a happy birthday.

Galen laughed, slowing his swing by dragging his shoe soles against the wood chips, and I did the same. I thought he might be cold. I thought maybe he was ready to head back home.

But then Galen reached inside of his shirt pocket and handed me a jewelry-sized gift box. It was wrapped in violet tissue and tied with a metallic black ribbon.

“Does it bite?” I asked, looking at him sideways.

Galen shook his head. “You see any airholes?”

I frowned. “It’s not dead, is it?”

He shook his head again, innocentlike. “Nope.”

“Will it publicly humiliate me in any way?”

He laughed again, this time nervously.

Suspicious, I thought. I almost asked another question, but I caught a glimpse of pink rising on his cheeks. It’s just the cold, I told myself. But I could’ve sworn he was blushing. To the best of my memory, Galen never blushed.

Opening the box, I lifted a necklace from the puffed cotton. A black suede pouch, in the shape of a half-moon and as small as my thumbprint, lay between dangling leather ties. Seed beads in daybreak colors—crimson, yellow, and burnt orange—lined the curving seam, sealed with white crisscross stitches. Larger daybreak-colored beads flanked the pouch, bordered by even more beads—two plastic midnight blues and two scalloped metal silvers. The necklace smelled smoky, bittersweet, and granny-ancient.

I remembered seeing it last June, displayed on a Lakota trader’s table at a powwow in Oklahoma City. Aunt Georgia had taken Galen and me on a road trip to visit family, and he had trailed after me down crowded aisle after aisle.

Later, with fingers sticky from an Indian taco, I’d focused my camera on a girl turning with a rose-quilted shawl. I shot her two ways, first to capture one footstep, one flying rose, and then slower to preserve the blur of her dance, the rhythm of the Drum. Meanwhile, Galen had ditched me on a popcorn run to shop.

Tying the necklace around my neck, I realized it was the furthest thing from what I’d been expecting, that it was the kind of gift you might call romantic.

Leave it to Galen to be the brave one first.

His blue eyes had lost their usual mischief, and it was clear that something had changed when he looked at me. But right then, I didn’t have the words, and I was pretty sure he didn’t, either. So we did the only thing we could have. We began soaring again.

As the swing carried me up, I had to bite the insides of my chapped lips to keep from grinning. My toes tingled with stardust. Even if I chickened out at midnight, this let me know I could bide my time. Maybe Galen and I would be like Gramma and Grampa Scott, high-school sweethearts who’d never belong to anyone else.

I told myself that if Galen had ever looked at another girl the way he was looking at me, it had just been for practice. It absolutely didn’t count.

Later, Galen shot by me on his swing, yelling, “I’m going to jump.”

“You’re too high,” I said, trying not to sound like his mother.

Galen let go of the chains and flew, shouting, “Happy New Year!”

Snow fell like parade confetti. “Ten from the Chinese judge,” Galen called, sticking the landing and raising his hands high. “Nine point five from the French.”

He jogged down the hill, and Chewie circled him, tail wagging.

“A lousy eight from the American,” Galen added, spinning in the soccer field with his arms outstretched. “What kind of loyalty is that?”

I heard a distant siren and the flurry of fireworks. Dragging my high-tops to slow myself, I fiddled with my camera strap. My lips itched, and my heart did a two-step.

I rose from my swing. It was happy birthday time.

Broken Star

FROM MY JOURNAL:

The KEEP OUT sign hadn’t stopped Galen, or stopped me from following him.

Walking home from Vacation Bible School, we broke a batch of no-no’s to check out the new city hall construction site. He tripped over a two-by-four and tumbled into a big ole hole, landing in a muddy puddle. A rescue attempt landed me in there, too. By the time we shimmied out, well, piglets would’ve been more sanitary.

Later, in my driveway, Galen told Mama, “It was my fault.”

When she folded her arms, I added, “We’re sorry.”

In the moment that passed, I said a quick prayer for forgiveness. Then Mama laughed and opened her arms wide. “Partners in crime,” she declared, drawing us close, not caring about messing up her own denim jumper. “You’re still in trouble, you know.”

That hug with Mama and Galen, that’s my safest memory.

JANUARY 1

The ringing phone stirred me, and I stretched my legs under my Broken Star quilt. I could expect Grampa Berghoff and Fynn to cater to all of my whims for the rest of the day, my birthday, the first day of the new year.

Grampa drummed my door. “You up?”

My yawn landed in a smile. We had our own traditions. Birthdays meant breakfast in bed. Orange juice, blueberry pancakes, and, for dessert, a box of Cracker Jacks.

I pushed up against my canopy headboard. “Enter.”

For the first time, no room service. My hands curled around the edge of the quilt. If somebody didn’t hurry up with breakfast, we’d be late for church. “Where, pray tell, is Our morning meal?” I demanded, pretending royal indifference. “Our orange juice, Our pancakes, Our . . .”

Grampa came in, wearing his ratty bathrobe, fuzzy slippers, and a look that had nothing to do with celebrations. “That was Mrs. Owen on the phone,” he said. Grampa knelt at my bedside, and his cold hands cradled my warm ones. “This is going to be hard, but . . . I’d best just spit it out. She called to let us know that Galen passed away last night. It was an accident, Rainbow. Nobody’s fault.”

My eyes grew heavy, fuller, like sponges. My lips and fingertips chilled. I felt the news clear to the most locked-down places inside of me, clear to that part I thought had died years before with my mom. And that was before it began to make sense.

When Galen had left me the night before, it had already been past his curfew. He’d said it would be faster for him to run straight home than return to my house and get a ride from Fynn. Two blocks, I’d figured. No problem. What could’ve gone wrong?

I whispered pieces of questions, and Grampa offered parts of answers.

He explained how some bottle rockets had caught on the roof of the Tischers’ barn and how the volunteer firefighters had been called out. By the time they’d headed back to the station, the streets had turned to ice.

The driver said that he never saw Galen, that Galen just ran right into the road. Even if the driver had tried to brake, with the ice, it would’ve been too late.

For a long while, I didn’t mouth anything but the word no. Still, I knew it was true, because Grampa had told me, and if he could, Grampa would protect me from any hurt.

But I don’t hurt, I told myself. Though my body was still shaking, my eyes had suddenly gone dry.

Six Months Later

FROM MY JOURNAL:

Mrs. Owen called me twice on the day Galen died, once the next day, and texted three times the day before he was buried at the Garden of Roses Cemetery. She’d heard what the volunteer fire department had to say. She’d wanted to talk to me about what had happened that night and about her plans for Galen’s funeral.

I refused to respond, and Grampa told her I wasn’t ready for talking.

&

nbsp; I’m still not.

In fact, I was the only person in town who didn’t go to the funeral. My ex–second-best friend spoke in my place. Queenie read a poem she’d written for the occasion.

Fynn told me; that’s how I know. I didn’t ask, but it’s hard not wondering what Queenie said that day.

JUNE 26

As my laptop booted, Fynn was sitting across the kitchen table, looking up at me from his coffee.

When I didn’t answer, my big brother set down his Starfleet Academy mug and said, “Aunt Georgia called this morning. Her grandnephew Spence is coming up to visit from Oklahoma City, so she’s pushing back the start date for Indian Camp.”

I couldn’t believe Fynn hadn’t given up. For weeks, he’d been dropping hints about my signing up for the program Aunt Georgia was coordinating. But there was no way. It wasn’t that I didn’t appreciate her efforts. It was just that I hadn’t been out and about in a long time. I wasn’t ready to start with Indian Camp.

Granted, I felt a little guilty.

Aunt Georgia had lived in Hannesburg my whole life, ever since marrying her husband, who she first met on a visit with Gramma to see then-baby Fynnegan. Their mamas, Aunt Georgia’s and Gramma Scott’s—my great-gramma Melba—grew up together at Seneca Indian School in Oklahoma and had stayed best friends.

Aunt Georgia had been there when Mom was born at Gramma and Grampa Scott’s house in Eufaula, right there with the midwife in the bedroom. She’d been there when I was born, too, in the local base hospital.

But Indian Camp? It sounded like the kind of thing where a bunch of probably suburban, probably rich, probably white kids tromped around a woodsy park, calling themselves “princesses,” “braves,” or “guides.”

Not my style. For that matter, not Aunt Georgia’s. But the last couple of months, she’d been talking about doing this summer camp for Native kids in Hannesburg.

It sounded like some kind of bonding thing. Or maybe just bait to lure me out of the house. No, I was being full of myself. More likely, it had something to do with the way Hannesburg schools taught about Native people and, because of that, the way it sometimes felt to be Native in Hannesburg schools.

Ancestor Approved

Ancestor Approved Rain Is Not My Indian Name

Rain Is Not My Indian Name