- Home

- Cynthia L. Smith

Ancestor Approved Page 4

Ancestor Approved Read online

Page 4

“That’s good,” I said, and put my arm around her.

“Susan,” Uncle Lanny said. “I’m gonna drive a loop around Tulsa before we have to stop again. Maybe we’ll make it to Missouri.”

“I think you’re dreaming,” she replied.

“That’s why we gave ourselves two days plus,” Jay said, from his seat right behind me.

“Jay, weren’t you in the back of the bus?” Susan asked.

“I was in the back of the bus,” he said. “But when a lady as pretty as Mrs. Simmons needs help, a true Choctaw gentleman stays close by.”

I looked at Susan and we shared a nice smile.

The next twenty miles passed quickly. The road twisted through the western edge of the Kiamichi Mountains, surrounded by trees sprouting the first signs of early spring leaves.

As we drove by a grove of pine trees, a fat pine cone popped against the window next to me—and a thought popped into my head.

The nice boy at the cash register didn’t ask me for any change.

That’s what she said.

“Mrs. Simmons?” I asked.

“Yes?”

“Did the nice boy at the cash register give you the credit card back? After you bought the snacks?”

“Why, no, he didn’t,” she said. “I bought the snacks with the card and he said it was enough.”

My jaw dropped and my eyes grew big in disbelief. “Jay, are you listening to this? Susan?”

“Give me a minute,” Susan said. “I have family phone numbers for everyone. Maybe I have her grandson’s number.” She scrambled through notes on her phone.

“What is your grandson’s name?” she asked Mrs. Simmons.

“Gabe, his name is Gabe Simmons.”

In less than a minute, Susan had him on the line. “Hello, Gabe. This is Susan Fellabush. I’m helping out on the trip to the Michigan powwow. Yes, she’s fine,” she said. “I’m calling about the credit card you gave her for the trip.” There was a brief pause. “Oh,” she said, with tension in her voice, “it was a debit card. How much was in the account?”

Another pause, and the bewildered look on Susan’s face told me everything I needed to know. The “nice boy” had stolen the debit card, and the only question was how much did he steal?

Susan tucked away her phone and turned to me. “Four hundred dollars,” she whispered.

“We can’t let him get away with it!” I shouted.

“What should we do now?” she asked.

“I know what the Choctaw Lighthorsemen would do,” Jay said. “He’d be arrested before sundown.”

How can you not love these old Choctaw folks! They know our history, our survival stories! The Choctaw Lighthorsemen were the only real law in the old Oklahoma west, for half a century.

“Well, Jay,” I said, “we’re not the Choctaw Lighthorsemen, but we can’t let him get away with it. Uncle Lanny,” I said, leaning over him, “it’s time to turn this bus around.”

“Oh, sure thing, Luksi,” Uncle Lanny said. “My job is to do everything you say.”

I didn’t know what to do, but Jay MacVain did. He stood up and spoke in a serious voice. “Lanny, maybe it is time for you to hand the wheel over to someone who understands and cares about these Choctaw Elders.”

“Maybe me,” Susan said, standing up beside him.

I wasn’t about to be left out of this ceremony.

“Maybe me,” I said, squeezing between them.

Jay started it first, a soft little Choctaw laugh, and soon Susan joined him, then Mrs. Simmons, and finally everybody on the bus dove in! A louder, funnier Choctaw laugh I’ve never heard!

“Hoke, all right already,” Uncle Lanny said, joining in the laughter. He pulled the bus into a shopping center parking lot and turned it around.

“Now what do we do?” he asked Susan.

“Drive back to the store, and hurry!”

Trees sped by and road bumps bumped and soon we arrived.

“Let me take care of this,” Uncle Lanny said. I saw him clench his fists as he stepped from the bus. I would not want to be that cashier, I thought.

Susan went online and found the number to the sheriff’s department. She called and reported the theft of the card. “And please call and let me know whatever you find out about the cashier,” she said before hanging up.

I slipped through the open bus door and was about to follow Uncle Lanny to the store, when something caught my eye. A beautiful hawk flew from a huge old oak tree beside the store. I felt a soft breeze on my neck, and I knew that somebody was trying to tell me something.

“Yakoke, thank you,” I whispered.

I walked beneath the tree and saw the cashier climbing down the tree trunk. I waited. I expected him to see me and run away. Instead, he approached me with his hand outstretched.

“Please take this and give it to the lady,” he said. He opened his palm and there lay the debit card. I took the card and waited for him to speak.

“Yakoke,” he said, which told me he was Choctaw.

“Why?” I asked him. I could have told him, The card was a gift from her grandson, or She is a Choctaw Elder. How could you do that? But the simple word why seemed to be enough.

“I made the worst mistake of my life,” he said. I watched as he closed his eyes and his chin sank to his chest.

“Why?”

“College. I am flunking out of college. I don’t have enough money for books. It’s spring break now. I’m working full-time at two different jobs. But I still don’t have enough money.”

He waited for me to reply, but I said nothing.

“I made a terrible mistake,” he said. “What should I do?”

“If you want to face what you did,” I said, “take the card back and give it to Mrs. Simmons.”

He met my eyes and slowly nodded.

“I’ll get her if you return to the store,” I said.

“I can’t go back there,” he said. “I’ve already called in sick, and somebody is on their way to replace me.”

A sudden blaring sound of sirens came from the front parking lot. WHIRRRRRRRRRR.

“Sounds like things just got a little more complicated,” I said. “The cops have arrived.”

“Time to confess,” he said. Then he turned to me, and with a sad smile said, “My name is Jimmy.”

I handed him the debit card and he walked from the tree to the front of the store. Uncle Lanny was standing between two policemen on the sidewalk.

“There he is,” he said, pointing to Jimmy.

Mrs. Simmons, aided by Jay MacVain, stepped down from the bus. “Oh, there is that sweet young man,” she said.

Soon we all gathered in a tight circle, surrounding Mrs. Simmons and Jimmy. “I want to return this to you,” Jimmy said, handing her the card.

“Yakoke,” she said, batting her eyelashes and turning her head to smile at the cops.

“Do you want to press charges, ma’am?” an officer asked. “Just say yes and we’ll take him to jail.”

“Take this young man to jail! Why would you do that? Maybe you need to learn some manners,” Mrs. Simmons said.

“Looks like you lucked out this time, young man,” said the officer.

I pulled Susan aside and told her what Jimmy had said. She nodded and turned to the officers. “We’re fine here,” she said. “Everything is under control.”

“If you’re certain, then we’ll be on our way,” said the lead officer. Glancing at Jimmy, he added, “But we’re never far away, and you’ve got our number if you need us.” The policemen then climbed into their patrol car and sped away.

“Let’s get back on the bus!” shouted Uncle Lanny.

“Not just yet,” said Susan. “Jimmy, we need to talk. Follow me.”

She led him to the base of the oak tree, just as a shadow passed over me. I looked up and saw the hawk land on a limb high overhead.

I had no idea what Jimmy said to Susan, but they talked for a long time. Finally, Susan gra

bbed her phone and waved what looked like a friendly finger at him.

The strangest day of my life had only just begun!

Susan returned to the bus with her arm wrapped around Jimmy. “It’s all arranged,” she said, “and the Choctaw Nation has approved it. Jimmy has been hired to travel with us, to help Lanny and me care for our passengers.”

“Yes!” I shouted.

Uncle Lanny gave me a hard stare. “I hope you know what you’re doing,” he said to Susan.

“Sir, I will be the hardest-working young Choctaw you’ve ever seen,” Jimmy said. “At least I’ll try to be.”

Even Uncle Lanny had to smile.

Jimmy leaned over and whispered in my ear. “The tribe is also paying for my books, and I’m going to apply for a scholarship.”

In half an hour we were once again on our way to Michigan. To the Michigan powwow!

Two days later, after a dozen restroom stops and two laughter-filled nights of Choctaw Elders wandering about hotel lobbies and asking, What room am I in?, we pulled into the powwow parking lot.

We arrived four hours later than we’d planned. It was already eleven o’clock in the morning, and I knew I had to hurry to make the Grand Entry. I dashed from the bus with my clothing bag slung over my shoulder.

The dressing room was crowded, of course, but I’m a skinny little Luksi. I don’t need much room. I scrambled out of my jeans and jumped into my dad’s white leather britches, pulling tight a blue-and-yellow beaded belt. I dove headfirst into his old Choctaw shirt with rattlesnake diamonds on the sleeves. With deerskin moccasins on my feet and a bright red feathered headband, I felt ready to go. The drums sounded so powerful and strong, booming through the walls.

Follow the kid in front of you,

Follow the kid in front of you,

Just follow the kid in front of you,

I whispered to the beat of the drum.

I stepped and stomped to the beat of the drum. As I neared the entrance to the arena, I saw a throng of Choctaw Elders smiling and clapping. They had formed a hallway of Choctaw Elders, plus Susan, to give me strength before I entered the arena!

At the head of the line stood Uncle Lanny, and across from him our newest Choctaw friend, Jimmy. And they were chanting a new song—to welcome me.

Luksi achukma, halito,

Welcome Little Turtle!

We are Choctaws,

We are one,

Warriors of Forgiveness!

“We are warriors of forgiveness,” Uncle Lanny whispered in my ear as I danced past him.

“Warriors of Forgiveness,” I sang to the rhythm of the drumbeat. “Warriors of Forgiveness.”

I knew our lives would never be the same—Jimmy, Mrs. Simmons, Jay MacVain, Susan Fellabush—our lives would never be the same.

Uncle Lanny and Jimmy were our new leaders, our Warriors of Forgiveness.

Brothers

David A. Robertson

Aiden enjoyed drives like this one. Not city drives. On the highway, toward anywhere far away. Where he and his foster parents were going now, there wasn’t much to look at, not at first, but it wasn’t all about scenery. It was being away from so many cars, and traffic lights, and signs, and houses, and people. They were headed south, then southeast, on their way to Michigan. Until Wisconsin, the land was flat and wide, the sky endless and enormous. As ceaseless as the prairies.

It was sixteen hours from Winnipeg to Ann Arbor. The flatlands and open skies would accompany them for at least seven hours of the trip. Aiden did only a handful of things during the long drive, which was broken up by bathroom and gas stops, and a quick hotel stay about halfway to Michigan.

The one constant was reading. He had a stack of books at his side, along with a water bottle and a bag of snacks his foster mother had prepared for him. His foster parents had their own water and snacks at the front of the car.

The thing he did during the first hours of the drive each day lasted only as long as his device’s battery life. He had been permitted to download a few games onto his iPod, and to play those games for as long as his battery lasted. This was how his foster mother monitored his screen time: He started each day with the beautiful sight of 100 percent battery life, but once the iPod was dead, it was dead. There was no going back. Aiden thought it was unfair.

This meant that for a good five hours on the first day, all he had to do was read, because after not too long the prairies were boring, even the sky. You could only make clouds into so many shapes.

But once the car got deeper into Wisconsin on the second day, as the prairies were left behind, it was like they were in a whole other world. There were actually things to look at. Like, the land actually had contours. Hills. There were more trees, fewer farmers’ fields. So during the last hours, even before his iPod died, Aiden traded time between staring at a screen or, later, the page of a book and staring out the window. And his mind wandered while he took in the pretty new landscape. Aiden’s foster parents, who were white, were taking him to a big powwow, and he kept thinking about the life he’d missed, but still might be able to find.

A few months earlier, he’d been connected with his birth parents. They lived in a Cree community in Northern Manitoba. Aiden found out that he had an older brother named Vince, too. They messaged together for weeks, and then one day Vince invited Aiden and his foster parents to the place they were headed now. Along with being a computer nerd, a fellow sci-fi enthusiast, and a lover of all things eighties and nineties, Vince was an accomplished Grass Dancer. This was going to be Aiden’s first powwow. He’d only just started to take lessons in the city after finding out Vince danced, and had only seen the different kinds of beautiful dances, the vibrant clothing worn by Indigenous people while performing them, on YouTube. Vince said that he’d taken part in so many powwows that he couldn’t even count them; he was seventeen, five years older than Aiden. Vince had told Aiden lots of things over text, about their home community, their birth parents, what life was like there, and dancing. Aiden was most excited to see his older brother.

They finally pulled up to their hotel. It was late in the afternoon, and everybody was tired. They checked in, ate a quick meal in the restaurant, and turned in for the night. Aiden’s foster parents were asleep almost as soon as their heads hit their pillows, but Aiden had trouble falling asleep. He was really tired but kept thinking about the same things he’d thought about in the car. They weren’t driving anymore, but his mind was still racing. He had a new window to stare out of: the hotel room window, where even though it was night, the streetlights outside painted the curtains orange. Aiden stared until his body and his brain gave up, and his thoughts turned to dreams.

Aiden devoured a free continental breakfast in the hotel lobby the next morning. The good kind. There was the regular: bagels, bread, cereal, bananas, apples, instant oatmeal. But there were also waffles, omelets, and sausages, and nothing was safe from his stomach. While eating (his foster parents described it as inhaling, not eating), he noticed how many Indigenous people were lining up to get food and sitting at the tables. This must have been where people from out of town going to the powwow were staying. Aiden had never been around so many people like him before; there weren’t a lot of Indigenous people in his community or at his school. He started to imagine them later on in the day, when many of the breakfast-goers would be in regalia.

Aiden hadn’t brought anything special to the powwow himself. He’d never owned regalia. When he took lessons, it was just in regular clothes. He’d asked his foster parents to buy him an outfit, or else what was he going to dance in? But they’d flatly refused, telling him only, cryptically, that he wouldn’t need anything from them. So after breakfast he put on sweats and a sweater, and they were off from the hotel to the powwow.

There was a parade of cars heading from the hotel and around the outskirts of the city toward the powwow, like they were in some kind of procession. Aiden spent the drive checking out license plates to see where everybody was from,

because the scenery wasn’t all that exciting. There were churches and schools and farmland on the left, nothing different than in the country around Winnipeg, and more of the same on the right. Nothing much changed until they drove through a residential area before pulling up in front of Skyline High School, where the powwow was taking place.

It was a huge school, a building constructed out of metal and glass and brick, and Aiden couldn’t think of a bigger school in Winnipeg. But still, as he looked around and all he could see were the parking lot and the school, something didn’t seem right.

“Hey, aren’t we going to a powwow?” Aiden asked.

“We are,” his foster father said. “This is where it is.”

“Is there a field behind the school or something?”

With such a big school, he supposed that it wouldn’t be surprising if the school had an equally big field. The only other times he’d been to the States, it had been to play hockey, and the hockey arenas were all supersized too.

“No, Aiden,” his foster mother said. “The powwow’s inside the school, in the gym.”

“Inside the school?” Aiden repeated.

That didn’t sound right at all. All the powwow videos he’d seen were in fields. Not in gyms. He was in a gymnasium almost every day for phys ed. For basketball. For volleyball. For beep tests. Floor hockey. Ultimate. All those things, but not powwow dancing.

They had arrived with lots of time before the Grand Entry at noon, so after going through the admissions gate, they decided to walk around the vendor floor to see all the things that people had for sale.

“When am I supposed to dance?” Aiden asked as they walked from the front of the school to the back, where the vendors were.

There were two times for intertribal dancing on the first day of the powwow. One started right after the Grand Entry, and Aiden did not want to dance that early. He was already nervous and was convinced that if he had to dance in front of all the people in the gym right away, the big breakfast he’d eaten wouldn’t stay in his stomach for long.

His foster mother looked sympathetic, probably because Aiden looked as sick as he felt. “At one thirty p.m.”

Ancestor Approved

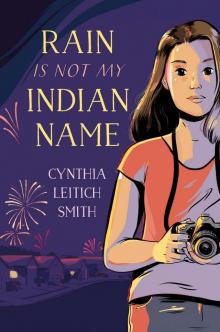

Ancestor Approved Rain Is Not My Indian Name

Rain Is Not My Indian Name