- Home

- Cynthia L. Smith

Ancestor Approved Page 14

Ancestor Approved Read online

Page 14

Listin tried to put the key in the door. The entire car door was coated with ice. He tried to scrape it, breathe on it, and rub his fingers over it. Yet nothing, nothing worked. Until, well, until . . .

He reached into his jacket pocket for gloves, but instead grabbed a thin plastic object and pulled it out. The thing I put in there: a slim white lighter with the words Native Pride on it. Listin looked confused as the ice rained down on him. I know Listin really well. I could just imagine what he was thinking: Joey did this little prank! Wait till I tell Ma he’s playing with lighters . . . I’ll make sure he—

He grabbed hold of the lighter, and suddenly he felt something like a warm breath cup his ear, whispering, “Mikwam.” At the same time, Listin understood that mikwam meant “ice” in Ojibwe. He’d never heard that voice before, that calming voice.

He looked at the lighter, quickly flicked it on, and let the flame warm the door lock.

The ice melted enough so that Listin could put the key in and unlock the car door! He stayed in the car until the weather cleared.

I saw it all from the front door of the school.

Ice turned back into rain as it fell in sheets. Then along came a change in the color of the sky. It turned from gray to an ominous yellow-green color. Uncle Mike was heading outside to start clearing the ice from the sidewalks. But before even he finished scraping a few feet, the hair on the back of his neck felt like it was being electrified.

Slowly, a whining sound began to gather intensity. With fear, he turned around to look west of the school football fields. Quickly approaching was a small funnel cloud whirling from the sky, almost touching the ground.

Uncle Mike, who used to be a volunteer firefighter back when he lived in the Upper Peninsula, knew when danger was approaching. He grabbed his walkie-talkie to get ahold of the office to warn the school. Later Uncle Mike told me he was thinking: Why isn’t the siren going off? The siren is right there on top of the pole, only ten feet in front of the school.

He continued to fumble with the walkie-talkie and reached into his shirt pocket to use his cell phone, when he grabbed a thin metal object. The thing I’d given him earlier that morning.

Just then, he felt a soft blast of warm air, almost like a breath, as he heard, in his ear, “Wese’an,” said in an unfamiliar quiet voice. Instantly, as he held the small piece of metal, he understood this to be the Ojibwe word for “tornado.” Uncle Mike ran to the pole just in front of the school. He climbed, using the metal ladder attached to the pole to guide his way up.

At the top of the pole, he saw the tornado siren’s cover was coated with rust, and on top of that, it was encased in ice from the day’s storm. Its corrosion was preventing the sensor from connecting to the weather center’s computer warning system!

Looking behind him, he saw what looked like funnel clouds almost touching the ground next to the school.

That’s why it’s not sounding off! People need to hear this to know to take cover as they’re getting ready for powwow! Uncle Mike thought. He took the wirelike metal object that I’d given him, a large, straightened paper clip with a hook on the end, and shoved it under the plastic hood of the siren. The wire was able to punch perfectly through the rust and ice, into the hole on the siren cover, and freed it from being blocked.

Whir! The siren’s great thundering alarm caused Uncle Mike to fall fifteen feet back down the pole. Just before he slammed into the ground, that warm, soft breath enveloped him and gently floated him safely down.

I, along with some other vendors setting up that afternoon, watched this all from the school. I held my ma’s hand to calm her. But after a while, the green hazy sky seemed to clear, and I headed out the door to look around.

“Hey, Joey, where do you think you’re going?” Listin yelled as he walked around the corner of the school.

After all, he wanted to know what I’d been doing with a lighter. Seriously, I’ve never played around with fire, but Listin still didn’t understand that I gave it to him because he’d need it later. And he did.

Makwa came out of the school too, and I sighed and signaled that I’d help carry the rest of our stuff in. He led me behind the school, where our car was parked. I twisted my head up again with my ear tilted toward the sky.

With one quick movement, I grabbed two garbage bin covers next to us.

“Makwa!” I hollered as I threw one of the covers to him. Suddenly, the skies opened again with a crack of booming thunder.

As Makwa reached out to grab the makeshift shield, he felt a warm breath of air coming from the ground, saying, “Mikwamiikaa.” He’d never heard this peaceful but powerful voice before. Instantly, when he grabbed the garbage can cover coming at him, almost like a round plastic sled, he instantly knew that mikwamiikaa meant “hail.”

Hail that pelted him and everything in sight just then.

He lifted the shield above his head to protect himself, looked over at me, and saw me doing the same. Makwa leveled his eyes at me, and at that second, a breath of warm wind surrounded him, keeping the hail from pummeling him again.

Well, that warm breath, and the shield I gave him.

Seconds later, the hail stopped, and the ground was covered in an inch of pebble-size balls of ice. Makwa wasn’t sure what had happened to him. His head felt a little lighter now. And his heart, too. But, after all, I was his little brother. The one who everyone knew wasn’t “smart.”

He looked up at me, only a few feet away, and started to ask, “So, how did you kn—”

But I lip-pointed down the little hill we stood on. My brother had no clue what had happened. I took the plastic cover from over my head, held it in front of him, took a run, jumped, and flipped the sled under my body. I sailed past Makwa!

Makwa laughed and followed me, cruising down the hill on his “sled” too. We both rode on top of the hail.

At the bottom of the hill we cracked up at the sheer fun of the ride. I fell off my sled. It was the first time since our dad died that we lost ourselves in laughter. It felt good.

Makwa stood up, put out his hand, and helped me up. “Man, really, I’m not sure what just happened up there, Chief—I mean, Joey, but I . . . I’ve been a complete jerk to you. I just—”

“Eya, yes, you have been,” I responded, wiggling my eyebrows.

March can be warm and dry in the Midwest, or it can stink. The temperature outside can make you sweat buckets, or dump a blizzard on you with fifteen inches of snow. (And of course they never cancel school. Ever.)

On Saturday, the first day of powwow, it started out in the low thirties. Much better than the weather the day before.

So that morning, as we were unloading our stuff from the truck, I did it again. I stopped mid-step, turned my head, tilted an ear up toward the sky, and squinted my right eye.

I heard it again, but the sky was all clear now and told me all was safe. I stayed like this for a few seconds, then went to the school with my brothers.

My brothers asked me, “What’d you bring?” because they noticed my backpack slung over my shoulder. With some things inside. Just in case it happened again. Yet this time, instead of making fun of me, Makwa put me in a headlock (and didn’t twist hard) and Listin carried my backpack for me. I guess this was their new way of being nice to me. I’d take it!

During the first hour, as we set up our food stand, no one was paying attention to me. Makwa was trying to act all cool as the dancers walked past to enter the gym. Listin made sure we were doing our jobs at the fry bread stations right. And he tried to be sure to carry the heavy stuff when the women dancers walked by.

“Joey, your ma said you can come help me with the furnace right now.” Uncle Mike winked, looking at my huge pile of uncut tomatoes.

As I took off my apron, I looked up at the window in front of me, to make sure all was calm outside.

Most of our time that morning with my uncle was spent on maintaining the seventy-five-year-old furnace and ancient electrical system at the high s

chool. I held the flashlight while he tightened some wires. Dalton and his uncle, the assistant custodian, were helping, too. Dalton’s parents’ stand is next to ours. He’s the only kid, but the youngest of all his cousins. He totally gets what it’s like to try to dodge the teasing.

Uncle Mike tapped on the furnace. “Old boy, just hang on for the powwow this weekend.”

After the lunch rush, my mom gave us some free time, so I wanted to watch the dancers. But I’d left my phone (my mom’s old iPhone) in the car and wanted it to take some pictures. Really, I wanted to take pictures to tease Listin as he tried to talk to some of the girl dancers from South Dakota. He gets really nerdy when trying to talk to girls.

On my way out to the car I passed Maggie, and we smiled. I met her yesterday as we were setting up our fry bread stand. There was something about her eyes that had made me take a second look when we first met. I knew that look. That’s the look of sadness.

She told me her dad had died, too. It’s weird, but when you’re around someone who knows the same pain as you, it somehow lightens yours. But only for a few minutes.

As I began to head to the parking lot, I passed another window. I thought about what happened yesterday, and what just might have turned my life around. Okay, maybe it helped some people realize that I can read, but just in a different way.

So now you know the story, the one from that day before the powwow. Not a single person was hurt—only my brothers’ egos. The school and surrounding area only had a few small tree limbs scattered on roofs and driveways.

I told you about how I can’t read the way most kids do, but also the way I can read.

Uncle Mike said to me as we packed up to leave after the powwow was done, “How’d the other food stands look today, Joe?”

I winked. “Meh, the meat loaf stand looks mushy, peas are putrid, and the applesauce is acidic. Remember, we’re the World’s Best Fry Bread.”

Understanding how to read the sky is something nobody else can really do. And I can only do it knowing and learning my Native language. I get that I may never ace a big state standardized reading test in school. But it’s okay.

Uncle Mike continued, “Son, you can do it. But ‘it’ doesn’t mean a perfect report card in school. It means to keep following your path. Listen to what our language is teaching you. You did that, right? You could read the sky and helped all of us who didn’t know how to read that way. My boy, I’m proud of you.” Looking around at my mom and brothers, he tousled my hair. “We’re all proud of you.”

On the ride back to Minneapolis, Listin shut the sunroof cover. Fine. Whatever. Nap away, brothers. But then Makwa elbowed him, lip-pointed up, and flipped open the cover.

Smiling, I stretched my hand behind my head and looked up. At it. The thing I get. The sky I can read because of learning our language.

Miigwech, thank you, dear Creator. And miigwech, Ancestors, for keeping our Ojibwe language alive. Because of you, I can read . . . I can read the sky.

What We Know About Glaciers

Christine Day

Here’s the thing about having an older sister in college: it isn’t nearly as cool as it sounds. And that’s coming from someone whose sister used to be the varsity cheerleading captain, the homecoming queen, the president of the Indigenous Peoples Club, and the leader of a canoe family called the Future.

Her name is Brooke. She was all these things and more, until she left for the University of Michigan. Now she lives far away. She can only Skype for twenty minutes at a time. And all she ever talks about is her classes, her exams, and glaciers.

“That’s why recycling isn’t enough on its own,” Brooke tells our parents. The four of us are seated on the upper bleachers. The intertribal dancing is happening on the gym floor below in vivid, swirling colors. The dancers are smiling and stomping, straight-backed in their regalia. Brooke is raising her voice, shouting to be heard over the drums. “As a society, we must reduce our carbon emissions.”

So, she isn’t specifically talking about glaciers right now, but I promise, it’s coming. And really, who talks about this stuff at a powwow? No one I know. Not until my sister went from the coolest, sweetest, most beautiful and popular girl in our hometown of La Conner, Washington, to this weird, ice-obsessed person who loves coffee too much.

She reaches for the thermos at her feet. It makes me want to scream and tell her, It’s eight p.m. on a Saturday night, Brooke. Why do you need coffee right now? Why?

This is her fourth cup today. My parents and I flew in this morning, and she was drinking coffee when she met us at the airport. After we stopped by the hotel, she took us to the local café where she spends a lot of time studying. Then we came here, just in time for the Grand Entry. She filled her thermos once while I ate corn soup for lunch, and then again while our parents chatted with the Pendleton vendors.

Wait. Does my sister have an actual problem? What exactly does caffeine do to a person?

While Brooke continues her rant, I pull my cell phone out of my pocket. This caffeine question seems like the sort of thing Google was invented for.

And oh—

Increased heart rate? Insomnia? I’m scrolling and scrolling, and I don’t like this at all. One paragraph claims coffee can help to reduce headaches after “epidural anesthesia,” and I don’t know what that is, but I’m pretty sure Brooke doesn’t have it. But the rest doesn’t sound good. Does my sister know about these effects? Does she have any idea?

This is concerning. This is what happens when people move two thousand miles away from their friends and their family and their everything, for no real reason. This is what happens when you’re forced to live in a closet-size dorm room, and use communal shower stalls, and eat Top Ramen for dinner every night.

Brooke has dark rings under her eyes. Acne on her forehead. Her long brown hair isn’t as glossy or straight as usual. Like she forgot to brush it this morning. Her lips are chapped. And I don’t want to be rude, but—her breath stinks. I first noticed it when she leaned close to share her program with me, and—whoa. What even happened in there?

I lower my phone and am about to speak up, but Mom is talking now, and apparently, I’ve missed something.

“This is excellent news, Brooke! We’re so proud of you.” Mom pulls her into a big hug. Their woven cedar hats crinkle and tilt on their heads, their brims butting up against each other. Our cedar hats are handmade, traditional. We only wear them at powwows now, but in the old days, our ancestors used cedar for everything: canoes, longhouses, summer clothes, fishing nets, bentwood boxes, even baby diapers. Imagine stripping the soft inner bark from a cedar tree, and weaving the fibers tight enough so that no pee will come out. Imagine doing all of that, instead of just buying diapers from Costco.

My ancestors were legendary, honestly.

Dad raises his arms, palms turned in a traditional Coast Salish gesture. He’s murmuring words in Lushootseed, but his voice is deep and soft, and I can’t hear any of it over the pounding drums. If I had to guess, though, I think he’s telling my sister: You lift us up. You make our hearts happy.

Brooke smiles. She presses a hand over her chest. “Thank you. I’m so happy to have your support. I’ve applied for a scholarship; hopefully I’ll get some kind of assistance—”

Mom waves her worries away. “Even if you don’t get it, we’ll make it work. We’ll find a way to support you.”

I frown. “What are you guys talking about?”

Everybody turns toward me. Like they just remembered I’m here.

Mom says, “Weren’t you listening, Riley? Brooke’s going to study abroad in Greenland this summer!”

“Only for a few weeks,” Brooke says in a rush. “Summer semester is shorter than the others.”

I exhale. Relax a little. “You’ll be home for the canoe journey, right?”

“Well,” she adds sheepishly. “Nothing is certain yet, but I might spend the rest of my summer here. I’m interested in a local environmental nonprofit. If I

get the chance to intern there, I think I should take it.”

Our parents are beaming and puffed up with pride. I know I should be, too. This is my sister, after all. The girl who was voted “Most Likely to Succeed” in her senior year hall of fame. The girl who wasn’t popular for being rich or pretty or trendy, but because she is warm and kind and genuinely likable. She is the type of person who deserves everything good that happens to her. A real-life Cinderella. (If Cinderella wanted to pursue a double major in environmental science and sociology. She was a hard worker, so it’s possible.)

I want to be happy about this announcement. I swear I do.

But when I ask, “What’s in Greenland?” it doesn’t come out super nice-sounding.

“A cutting-edge research facility,” she says. “With a huge emphasis on local Indigenous leadership. Most of the faculty members come from Greenlandic Inuit societies. I’m going to contribute to an ongoing study, under their guidance.”

“It sounds amazing,” Mom gushes. “The perfect fit for you.”

“What do people study there?” I ask. “Why can’t you take summer classes online or—or something like that?”

“Because it wouldn’t be the same. If I really want to learn and grow, I need to learn from the best. If I want to make a difference in the world, I need to show up and be present.”

Wow. What an annoyingly Brooke-ish thing to say.

“We’re going to examine the Greenland ice sheet,” she continues. “It’s the second largest ice body in the world.”

Sure enough. There it is: glaciers.

Brooke is still talking. She’s comparing the size of this glacier in Greenland to the big one in Antarctica. She’s explaining the rates at which both are melting. She’s saying this is a crisis, that it will somehow impact everybody eventually.

Ancestor Approved

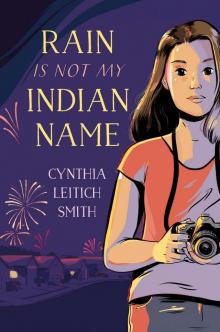

Ancestor Approved Rain Is Not My Indian Name

Rain Is Not My Indian Name